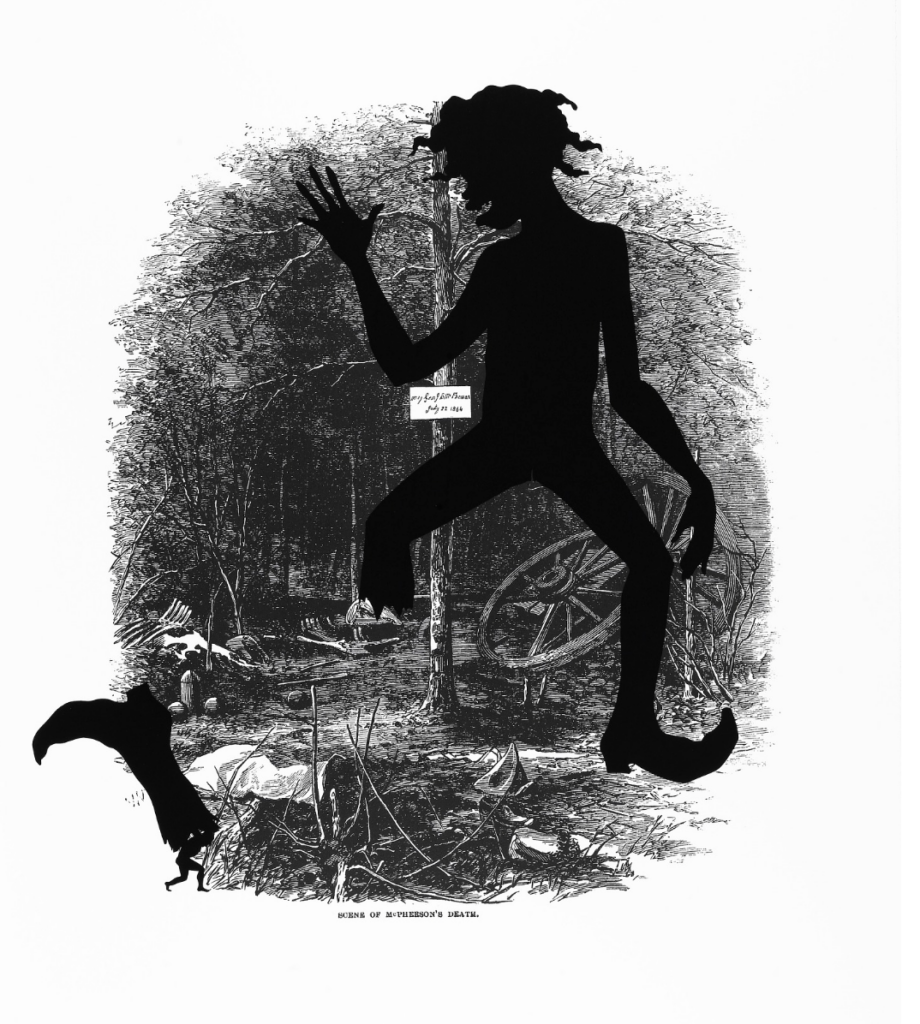

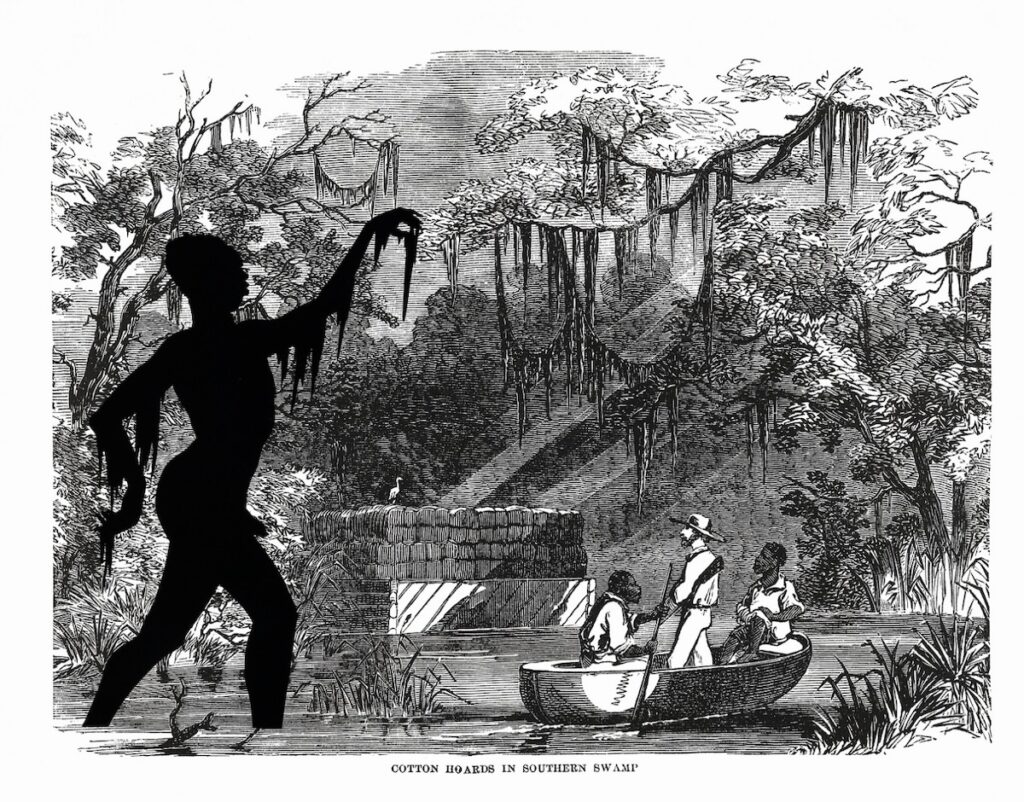

Kara Walker’s works are eerie. Her lithograph silhouettes straddle the line between memory, dreams, nightmares, and fantasy. How much of memory itself is a silhouette or an abstraction, something that lives inside the body as a formless darkness? Once moments in history pass, they’re gone, relegated to interpretation, often through images. Walker’s Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated), now on view at the Frick Pittsburgh, sees the artist taking Winslow Homer’s illustrations of the Union Army’s battles during the Civil War and superimposing shadowy silhouettes onto them. Walker uses the uncanny, humanoid shapes that don’t quite register as real both in her large-scale sculptures and in her two-dimensional works to play with the viewer’s expectations of what they’re seeing.

Kara Walker Casts the Shadow of History at the Frick Pittsburgh

Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated) originated at the New Britain Museum of Art in 2020, but the curatorial team at the Frick got to re-interpret the presentation of the show. At times, the silhouettes are indistinguishable from Homer’s original figures. In other moments, they dominate the image. Though there’s a quiet dignity to the simplicity of the silhouette, there’s an underlying feeling of grief and remorse. As contemporary viewers, we know that the triumphant soldiers Homer paints did not end suffering and oppression entirely. The Reconstruction period after the Civil War brought more discord and pain, even though the government did legally abolish chattel slavery.

Limbs are an integral part of Walker’s silhouettes. In the show’s final room, McPherson’s Death shows a Black child standing with her foot severed, the detached limb held up by another tiny Black figure. Walker wrote that “The silhouette says a lot with very little information, but that’s also what the stereotype does.”

Light and Shadow, Arms and Legs

The silhouettes in Walker’s work are not necessarily real people. At times, they appear as ghosts—in Cotton Hoards in Southern Swamp, one wanders a swamp nude with foliage swaying from his arms. That particular image shows beams of light making soft rectangles on the swamp floor through the treetops, yet unlike the two men in the swamp, Walker’s silhouette has no shadow. It stands on its own as a shadow of history.

Light itself, after all, is a part of how we perceive time, as increments of light and dark relative to each other. Without getting into quantum physics, Walker’s lithographs stand in Homer’s scenes outside of the past, present, or future, silent observers of human prejudice and hubris. Silent warnings not to repeat the same ills. But still, they watch as we do, possibly too busy celebrating incremental progress to see the larger picture.

Urgent Work

“These prints are twenty years old, and yet feel so urgent,” Chief Curator and Director of Collections Dawn Brean said. They’re reminders of moments of historical change, that our choices are consequential and that what seems far in the past is only a few generations away. Brean remarked that even ten years ago, the Frick likely would not have done a Kara Walker show—so this exhibition shows progress within the museum’s values and vision.

One unique element the Frick brings to the table is the use of guest wall labels from community members in Pittsburgh, including Yemeni street artist Haifa Subay, a refugee from a different civil war, and professor Shaun Myers, whose own ancestor fought in the Civil War in the US Colored Troops—only miles from one of the towns depicted in Homer’s prints. These bits of trivia add context to the work that grounds them in the present and keeps the show from being a repetition of what the New Britain Museum of Art already had. The museum will be holding a salon-style gathering for the guest labelists.

And though Walker’s art is some of the highest caliber in the world, and getting to see it firsthand is a treat for any art aficionados in Pittsburgh, it’s also worthwhile to learn about Black women artists in our own community. Artists like Tara Fay Coleman, Akudzwe Elsie Chiwa, Vania Evangelique, and Crystal Noel Jalil, to name a few, live and work in our city. Walker’s work shows that history is happening all around us, and how we participate in it is up to us.

Story by Emma Riva

Images courtesy of the Smithsonian Museum of American Art

Subscribe to TABLE Magazine‘s print edition.