When was the first time you saw the naked body as someone thought it should be, not as it is? Prior to the internet, museums were sometimes the first place that young people saw adult nudity. Museums provide an important site of learning and growth, where you can see what’s around you in context rather than in a vacuum. But that context can also have biases within it. In the Carnegie Museum of Art, while there are other depictions of the male body, there’s only one full-frontal male nude painting in the publicly viewable collection.

Why Is There Only One Male Nude at the Carnegie?

There is a plethora of classical statues of male nude figures in the Sculpture Court, embodying the Greco-Roman value of the beauty of youth in their chiseled, sumptuous muscles. The sculptures are beautiful, and they show that in the classical world, the ideal male body was young and supple, almost feminine. But by the nineteenth and twentieth century, depictions of the male body took a more macho approach—bulging muscle won out over innocent sleekness. Maybe this has something to do with the rise of industrialization and the increasing value placed on labor and productivity, but that’s a conversation for another time.

Beyond the sculptures, at the Carnegie nearly every two-dimensional representation of the body in a painting is a woman. Is the message, then, that women’s bodies are for ogling and men’s aren’t? While there isn’t a clear answer, it is fascinating look at how artists have chosen across the centuries to represent the body.

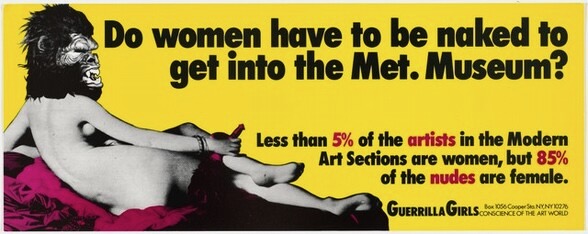

Activist group The Guerrilla Girls calculated that 85% of the nudes in the Metropolitan Museum of Art were women, but only 5% of the artists in their collection were male. This percentage is likely different in the Carnegie, given that work prior to the 1800s represents a smaller percentage of its collection than the holdings of the Met.

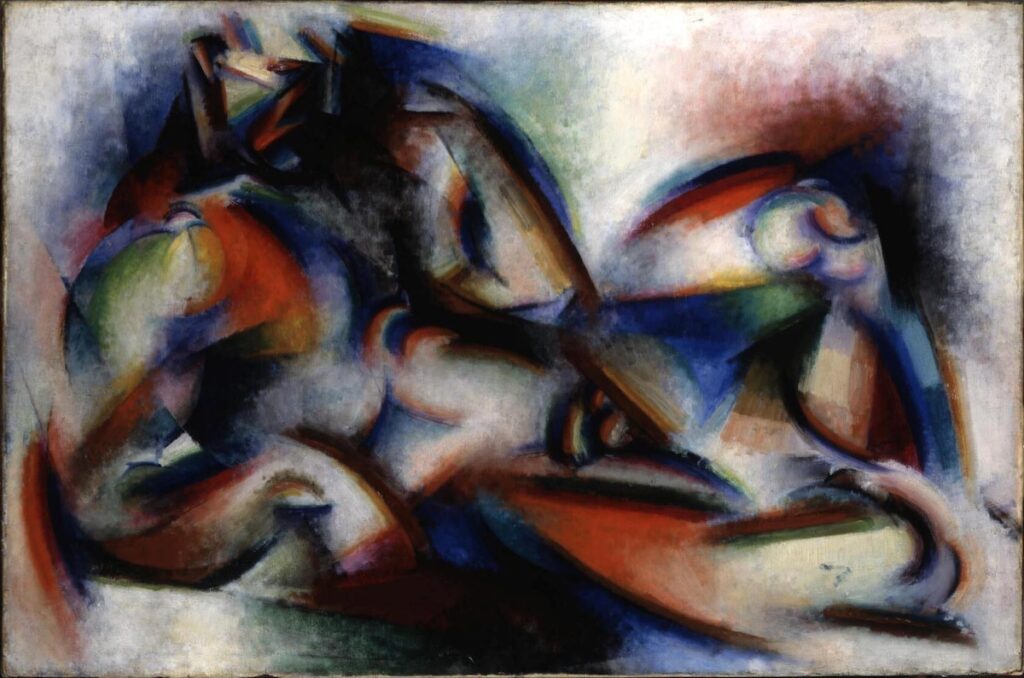

Stanton McDonald-Wright: The One Male Nude Painting

The one male nude painting is Sunrise Synchromy in Violet by Stanton Macdonald-Wright, in the back of the Scaife Galleries. This depiction of the male body is by a man. This is one of the through-lines of representations of male nudity—not only are there fewer of them, the ones you do see are by men. There’s very little female heterosexual sexuality from a female perspective.

Living Arts Foundation Fund and Patrons Art Fund.

And yet, Sunrise Synchromy in Violet is a deeply sensual painting, no matter the sexual preference behind its origin story. MacDonald-Wright coined the term “synchromism” for a new art movement that saw color and sound as similar phenomena. He and his contemporaries believed that like a composer, a painter could arrange color into a sort of symphony. Synchronism never really took off, but there is something marvelous about this painting. It feels tender and gentle in a way that classical male nudes often do not. That tenderness and gentleness then brings out a further strength and masculinity in the subject. MacDonald-Wright allows your imagination to wander across the body. It feels like looking at someone through their lover’s eyes.

Is Nakedness Inherently Sexual?

A contrasting painting of a woman, not very far away in Scaife, is Robert Henri’s The Equestrian. A female figure wears typically male dress, a bowler hat, riding boots, and a long coat, smiling at the camera. Yet, she’s unabashedly feminine, with a warm smile and soft eyes.

Henri used Waki Kaji, a Japanese woman, as the model for the painting, a controversial choice at the time. The Equestrian shows a woman fully clothed, but to me, it reads as having much more overt sexuality in it than the actual nearby female near-nude, The Toilet of Venus. Kaji’s stance and body language feels powerful. Nakedness does not equal sexuality. In fact, in more classical work, nakedness actually represented a kind of innocence. Kaji’s clothed sexuality forces a viewer to see her in fullness.

Female nakedness as a synonym for innocence did begin to evolve, but it sparked controversy. Contemporaries of French painter Gustave Courbet criticized him for the “ungainly” and “disheveled” appearance of a woman in his 1866 Woman with a Parrot, on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The woman in Courbet’s painting didn’t look like a goddess or a nymph , therefore her nakedness was unacceptable. But, with time, people came to accept the painting. Cézanne even carried it a small version of it in his wallet. The response to it, however, shows that there were boundaries and exceptions around how a woman’s body could show up in a painting. Men did not often receive such treatment.

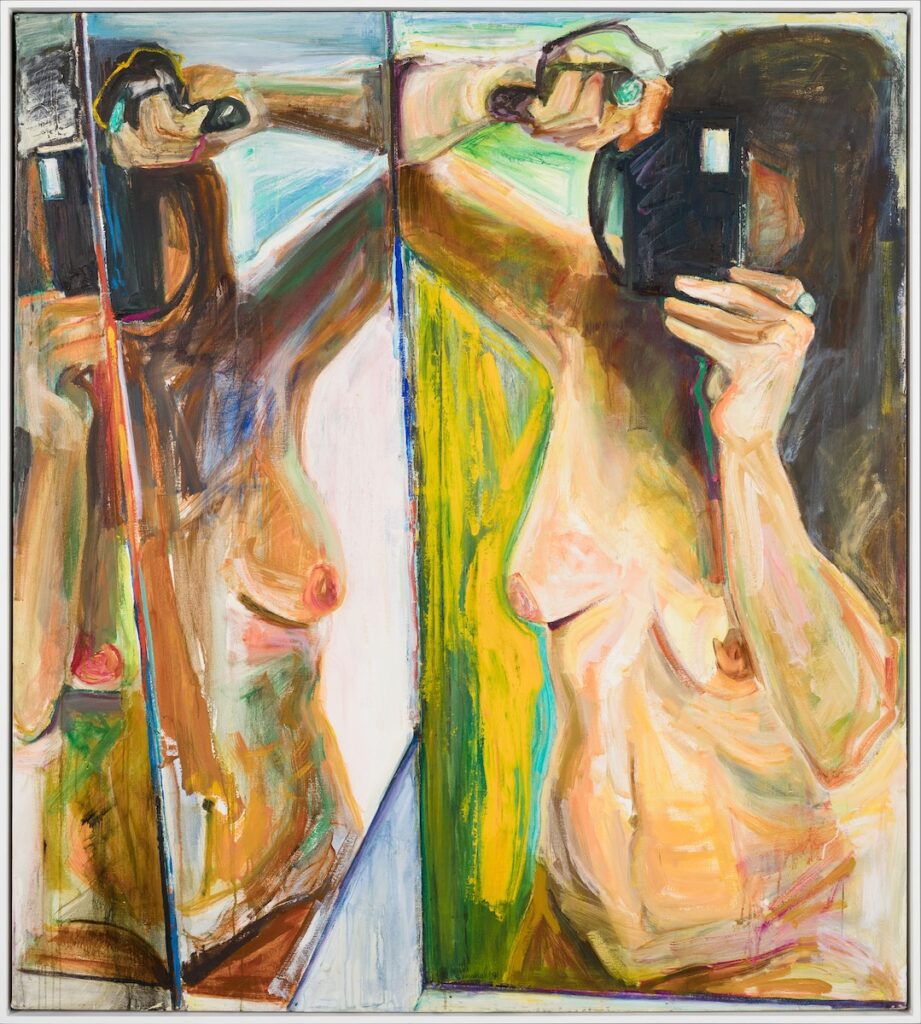

“You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman.”

For a woman’s perspective on a woman’s body, Joan Semmel’s Double Take is on the wall at the Carnegie right beside a space with a literal mirror, in a moment of curatorial sleight of hand. It provides an interesting visual to see a body in a mirror reflected in Heart Mirror at the center of the gallery. This painting shows the difficulty of really perceiving yourself as a woman, when your body is so often the subject and not the creator of the image.

It brings to mind Margaret Atwood’s remark, “You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur.” Semmel, however, made it her mission to get comfortable with painting nude portraits as a woman. She painted people in various states of desire and repose, including couples in intimate moments. If there can be such a thing as a female gaze, Semmel approached it.

Purchase, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Richard M. Scaife and gift of Paul Chanin, by exchange

© Joan Semmel / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

There are also women who painted male nudes. Flemish painter Michaelina Wautier painted men nude, and there is a subtle difference in aesthetic from her contemporaries. The male body looks more fleshed out, somehow. In the 1600s, nudes by women were uncommon, let alone nudes of men by women. But Wautier used male models to better understand male anatomy, to the point where historians misattributed her paintings to her brother, Charles.

Looking at Nudity in Context

In the scope of this inquiry, we’ve seen a male nude by a man, a female nude by a man (or several), a male nude by a woman, and a female nude by a woman. The social position with which the artist comes to the subject has become more relevant in discussions around contemporary art. Saying there is an inherent difference between how men and women paint risks essentializing art (and gender) down to a sort of mystical power rather than a diverse range of experiences.

Paintings are ways of seeing. The human body is as diverse as our perception of it, and maybe it’s better for young people’s first exposure to it to be different varieties of it in a contextual, artistic setting, rather than ubiquitously online. If you’re visiting the Carnegie with kids or young teens, it’s worth a conversation about why all those women are naked when the men are wearing clothes. Most painters were men, and they wanted to study the body. Because heterosexual men were the norm, their vision is what we see most of.

But Stanton MacDonald-Wright’s painting proves that beyond the literal realism of the body, most of us look best painted by someone who loves us. The true intimacy and beauty of nakedness is hard to let someone else look at—hence the abstraction. That, perhaps, should be the lesson, that to be looked upon with love is the greatest way to be seen.

Story by Emma Riva

Cover Image Courtesy of the Carnegie Museum of Art

Subscribe to TABLE Magazine‘s print edition.