At one point in history, Pittsburgh was America’s melting pot. The abundance of jobs brought a plethora of immigrants from Eastern Europe to work in the steel industry and settle in the city. But they often spoke their native language, an obstacle in this strange, new home with different cultural norms. Places like the Bulgarian Macedonian Cultural Center in West Homestead became community gathering spaces where recent immigrants could set a balance between assimilating into their new home and finding common ground, community, and shared values.

The Bulgarian Macedonian Cultural Center Sheds a Light on Immigrant Stories

Lambe Markoff founded the club in 1939. His grandson, Ed, is the president, and Ed’s daughter, Hayley Markoff Hinkle, serves as the secretary. Keeping a culture alive inter-generationally can be a difficult task with changing values and a shifting global landscape, but the Markoffs have kept the flame alive. “At the Center, we’re apolitical. We’ve navigated the changing politics and borders of Bulgaria and Macedonia from 1939 to now,” Ed Markoff said. They boast the title of being both the oldest, largest, and most active Bulgarian Macedonian club and the one with the largest collection of Bulgarian art, costumes, and jewelry in the United States.

Behind the Center’s unassuming doors in West Homestead is a deep well of history. When you walk in, a door downstairs reads MEXAHA in Cyrillic letters. A portrait of Lambe Markoff hangs on the rustic walls. You immediately get the sense you’re in a place of shared history. While the space is beautiful, it isn’t sterile the way a museum is. Even when no one is around, the room feels as if it still has the energy of past celebrations hanging in the air. “[MEXAHA] means a tavern in Bulgarian and Macedonian. The old immigrants would sit down there at the table and hand-roll cigarettes,” Ed Markoff recalled. The Center has a commercial kitchen and a liquor license and gets most of its revenue from donations and cultural events. It’s open to the public and free to look around, which both Markoffs encourage.

The First American Adoptee from Bulgaria After Communism

Markoff Hinkle was adopted from Bulgaria at 16 months old—the first Bulgarian child to be adopted by an American couple after the fall of communism in 1990. “The center is like a second home to me,” she said.

The social club also allowed her to learn about her home country and then in turn teach her own children about it. “In the 90th anniversary mural behind the stage, I was pregnant at the time, so I like to say both me and my daughter are on the wall here,” she said.

Folk Dance as Tradition

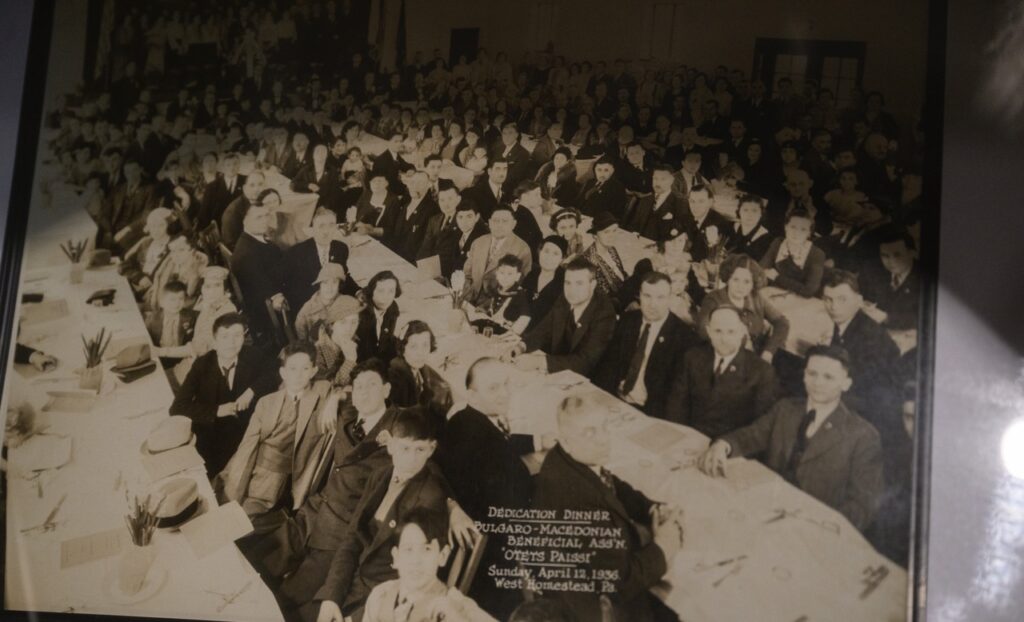

Folk dance is one of the Bulgarian Macedonian Cultural Center’s biggest programs. Pittsburghers might be familiar with the Tamburitzans, a folk dance group that’s performed in the city for more than 80 years.There’s a lot of crossovers between the Tamburitzans and the Bulgarian Macedonian Cultural Center’s group, Otets Paisii.

There are 40 dancers in the group, with most, including Markoff Hinkle, learning from a young age. It’s a real treat to visit the Center’s archival storage and see the radiant colors of the costumes for each dancer. Deep hues of shine with hand-stitched patterns on the fabric. “My sister and I danced in the very first Pittsburgh Folk Festival at Syria Mosque in 1955,” Markoff remembered. The group gets its name from a Bulgarian monk who documented the history of his people. They travel regularly to Bulgaria to perform or to learn more about their culture.

“Each region of Bulgaria has its own style of dance,” Markoff explained. “And Bulgaria and Macedonia are where Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Islam converge.” Markoff himself is the story of cultural convergence. His mother was Hungarian and his father was Bulgarian, making their union a mixture of the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox faiths. But both came to Pittsburgh as new immigrants and found common ground. At the time, it was common for Bulgarians to become bakers, which Markoff’s father did. You can still get Bulgarian baked goods at Jak’s Bakery in Bloomfield, or if you come to the center for one of their events.

A Place for Learning

Markoff Hinkle hasn’t been to Bulgaria yet, but takes Bulgarian classes and is enthusiastic about her culture. Spaces like the Bulgarian Macedonian Cultural Center celebrate not just the nostalgia of the homeland, but what immigrants bring to the places they come to. You can’t replicate Bulgaria and Macedonia in its entirety in Pittsburgh (though the topography of mountains and lakes is somewhat similar), but you can create something new, paving the road for a community’s future with memories and traditions of its past.

The Bulgarian Macedonian Cultural Center shows the power of immigrant communities to be safe havens. In a moment of political turmoil, when immigrants’ presence in our city and the country at large is in peril, it’s imperative to “look for the helpers” as the quote attributed to Fred says. Where are people welcome? Where do communities nurture and uplift each other? The heyday of Eastern European immigration to Pittsburgh may be over, but there are new community-building challenges to face. The Bulgarian Macedonian Cultural Center is free and open to the public and welcomes anyone with a curiosity about Bulgarian and Macedonian culture to look at their beautiful costumes or try some of their delicious food. “The culture is rich, and that’s how we’ve survived,” Markoff said.

Story by Emma Riva

Photos by Jeff Swensen

Subscribe to TABLE Magazine’s print edition.