A roundtable dinner gathers leaders of the Pittsburgh art world to imagine the future of creative life in a city still defining how to sustain those who shape it.

Imagining Pittsburgh’s Arts Sector in 2026 with the City’s Leaders

It began, as many generative conversations do, around a shared table: plates passed hand to hand, voices rising and softening, as artists and arts leaders imagined what creative life in Pittsburgh might look like in the years ahead. The library at The Mansions on Fifth glowed with candlelight and low conversation as TABLE’s Editor in Chief, Keith Recker, rose to welcome a gathering of the city’s most vital voices in the arts.

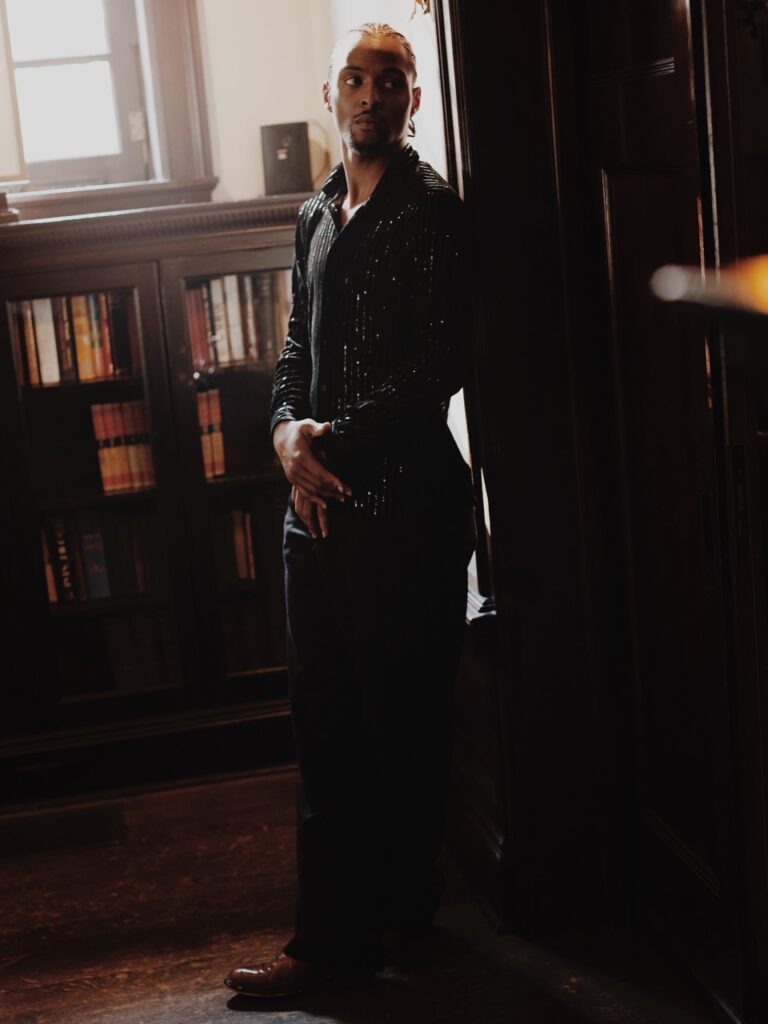

The dinner, co-hosted and convened with artist Shikeith, was conceived not as a celebration but as a moment of reckoning. Around the table sat artists, curators, and administrators who have shaped much of Pittsburgh’s cultural landscape—Jasmin C. DeForrest, Nicole Henninger, Leo Hsu, Anastasia James, Kilolo Luckett, Mario Rossero, London Pierre Williams, and Alisha Wormsley—invited to reflect on what it means to create, to sustain, and to tell the truth through art at a time when truth itself can feel embattled.

“This is a space for honesty,” Recker said, raising his glass. “Be brave. Tell the truth about what you’re seeing and what’s needed. Let’s have a real conversation.” His invitation landed not as a directive but as a challenge shared among peers—a call to speak candidly about the state of art and the city that shapes it.

As plates arrived, the hum of side conversation settled into a steady rhythm of exchange. What unfolded over the next few hours was both diagnosis and declaration: a conversation about creative courage, civic responsibility, and the fragile ecosystems that hold art in place.

Sustaining a Creative Life

For Shikeith, the question of sustaining an artistic life in Pittsburgh is inseparable from his own path. He recalled watching spaces like Bunker Projects grow from the ground up in 2013, and receiving an Advancing Black Arts in Pittsburgh grant that helped fund his documentary #Blackmendream, a film later listed by the Tribeca Film Institute as one of ten crucial works capturing Black life in America. He fondly calls this breakthrough his “Pittsburgh Cinderella story.” Yet even success, he reminded the group, doesn’t dissolve the challenges of sustaining a practice. Finding stability as an artist often demands a degree of restlessness and adaptability: “You have to go, you have to move,” he said, “but you also have to have a place to come back to.”

That notion of place, of the conditions that allow creativity to root and return, threaded through the evening. Artist London Pierre Williams described the ongoing challenge of finding a studio space that feels not only affordable but also right. For many, the struggle is less about resources than about resonance, the sense of belonging to a community that values experimentation as much as outcome.

What emerged was a portrait of a city still learning how to care for its artists: a place of promise, but also of precarity. Pittsburgh remains a haven for those seeking space to work creatively, yet the question lingers: how do artists stay once they’ve found their footing?

Comparing Pittsburgh to Other States

Returning to Pittsburgh to lead the Andy Warhol Museum after a decade in Washington, D.C., Mario Rossero saw in that tension the essence of the city itself. Artists and makers, he noted, are woven into Pittsburgh’s identity, their labor visible in everything from its public murals to its maker spaces and performance collectives. The challenge, he observed, lies in how to match that creative potential with visibility and support.

Jasmin DeForrest, who relocated from Detroit last year to lead creative initiatives at The Heinz Endowments, described Pittsburgh’s cultural landscape as strikingly rich yet uneven. “It’s a city of pockets,” she said—dense with talent, yet divided by geography and habit. “The opportunity lies in connection: how do we bridge those hills and valleys?”

Across the table, others nodded. The conversation turned to the city’s social scale—where there are often few degrees of separation between arts professionals—an intimacy that can be both a gift and a constraint. Sustaining creative life here, the group agreed, demands more than individual drive or good will; it requires networks of belonging that make art feel not peripheral to civic life, but essential to it.

The Vanishing Middle Space

When conversation turned toward infrastructure, the room’s energy shifted. The group spoke of the “missing middle”—that uncertain space between grassroots projects and major institutions where artists and arts workers often find themselves stalled.

Anastasia James, a Director of the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, has seen that gap from both sides. Having left the city early in her career to pursue opportunities elsewhere, she returned with a renewed awareness of what continuity requires. Pittsburgh’s challenge, she reflected, isn’t a lack of creative stock but a shortage of scaffolding, especially the middle rung that allows careers to take root rather than reset. It is no longer enough to repeat the old refrain of affordability; while Pittsburgh once promised ample space and low costs, that equation is changing fast, and the conversation must catch up.

Heads nodded in recognition around the table. Everyone knew the pressure points: rising rents, shrinking grant cycles, overextended institutions. But alongside the challenges came examples of how new models might emerge.

By the People, For the People

Kilolo Luckett, founding director of ALMA LEWIS, described designing her gallery’s residency program through consultation and community feedback. She asked dozens of peers what was missing from other residencies—how much time artists truly need, and what forms of care matter most. For Luckett, sustainability begins with listening and crystallizes with support. “We can’t underestimate the power of hustling, but we also can’t mistake hustle for sustainability.”

Her words carried a quiet resonance. The idea that generosity could itself be a structural tool—asking, listening, adapting—felt both radical and familiar. Rossero smiled across the table. “That’s actually a fitting tagline for Pittsburgh’s art world,” he said. “All you have to do is ask.”

The conversation broadened to include questions of accessibility and inclusion. Not everyone, the group noted, aspires to be a professional artist, nor should artistic participation depend on that ambition. Art must also be understood as a form of civic engagement, a way of learning, connecting, and imagining collectively.

Participants reflected on the power of craft traditions that continue to thrive here, and the need to connect those lineages to younger generations. Local institutions, they agreed, must act as intergenerational bridges: translating heritage into momentum, and local pride into national visibility. There was a shared sense that while the city has built remarkable artistic infrastructure, it must also learn to celebrate and historicize its own achievements, to document what has been made and protect it for the future.

Around the table, candles burned lower. Plates were cleared. What remained was a collective recognition that the health of Pittsburgh’s arts ecosystem depends not on scale, but on connectivity, the middle ground that holds everything together.

Art as Dissent, Art as Truth

By the time staff cleared the main course, the discussion had widened to the role of the artist in a polarized world.

Artists, several participants reflected, possess a rare civic function. They hold a mirror to their communities, reflecting both aspiration and unease. They are a source of solutions we haven’t yet found. “Artists understand and reflect our time and culture,” said Rossero. “They help us see ourselves, our truths, and our challenges. Through their lens, we gain a clearer view of our shared experience, and maybe even a deeper sense of compassion or connection to others.”

Kilolo Luckett described the artist’s task as inherently forward-looking. “Artists are always working in the future,” she said. “That’s what courage looks like. Stepping into what hasn’t been built yet.” Dissent, she added, isn’t an accessory to art; it’s one of its obligations. “Criticality is part of the artist’s DNA. We can’t heal what we can’t name.”

Alisha Wormsley reframed that courage in spiritual terms. “We are divining,” she said. “It’s ancestral.” For her, making art in difficult times is an act of worldbuilding, of summoning what’s missing and repairing what’s broken.

The group listened in a collective stillness that felt like reverence. Anastasia James reflected on her own early encounters with museums, recalling them as both sanctuary and occasional site of conflict—a reminder that institutions can hold us, but they can also create boundaries around who does and does not belong. The challenge now, she suggested, is to rebuild those spaces with care, to make them more porous and open.

In that moment, the dinner’s purpose was clear: if the arts are to survive, they must also transform.

Mapping What’s Next

As dessert plates appeared and coffee was poured, conversation turned toward the future. What could Pittsburgh’s creative landscape look like in 2026?

James spoke about Arts Landing, a four-acre downtown project that will merge performance and gathering spaces (including the first playground in Downtown Pittsburgh!) offering a pulse of public life in an area often quiet after dark. It is, she said, a vision of the arts as civic infrastructure, a place where daily life and creative life meet.

From there, the conversation moved toward a broader sense of orientation. Several participants reflected on the need to “make a map” to understand where the city’s creative community has been, where it stands now, and who has yet to be included in that picture. Wormsley added that such a map must be drawn with care, acknowledging histories of exclusion as part of the process of imagining what comes next. To chart the future requires an honest reckoning with the past and present.

The group also emphasized the importance of transparency, of understanding where the gaps lie in arts education, access, and space. Only through that clarity can Pittsburgh begin to strengthen its creative infrastructure in full.

And if mapping implies movement, Nicole Henninger reminded the group that progress also depends on nurturing the dreamers themselves. The sustainability of the city’s creative life, she noted, hinges on supporting artists not only as producers of culture but as people who are essential to the city’s civic imagination.

A Call to Show Up

As coffee cooled and the hour stretched late, the group circled back to a shared question: how can those who care about art—patrons, neighbors, readers—translate admiration into action?

Leo Hsu offered a profoundly simple answer. “Show up,” he said. “Bring a friend. If you go somewhere, go back. Create a relationship.”

Luckett encouraged curiosity. “Do something new,” she said. “Step into an unfamiliar space.”

Henninger reminded everyone that creativity belongs to all. “You’re already creative,” she said. “Keep going. That’s part of supporting the arts, too.”

Rossero added a practical challenge for patrons: “Support the production, not just the product.”

Recker, looking around the table, brought the group back to his initial invitation. “Take a risk,” he said. “Be bold.”

Chairs shifted. No one hurried to leave. Around the table—artists, curators, and cultural stewards who so often move in separate orbits—there was a rare sense of unity, a recognition that art’s survival depends on the courage to imagine together.

As the final cups were cleared and conversation softened, Recker raised one last toast that lingered long after the candles thinned to smoke: “Great art tells the truth—and that’s something we could all use more of.”

Participants

- Keith Recker / Editor in Chief, TABLE Magazine

- Justin Matase / Publisher, TABLE Magazine

- Shikeith / Artist, Visiting MFA Core Faculty, Carnegie Mellon University

- Jasmin C. DeForrest / Managing Director, Creativity, Heinz Endowments

- Nicole Henninger / Program Officer, The Pittsburgh Foundation

- Leo Hsu / Executive Director, Silver Eye Center for Photography

- Anastasia James / Director, Pittsburgh Cultural Trust

- Kilolo Luckett / Founding Executive Director and Chief Curator, ALMA LEWIS

- Mario Rossero / Director, Andy Warhol Museum

- London Pierre Williams / Artist and Adjunct Professor of Art, Carnegie Mellon University

- Alisha Wormsley / Artist and Assistant Professor of Art, Carnegie Mellon University

Story by Shawn Simmons

Photography by Shikeith, assisted by Mathias Rushin

Venue and Catering by The Mansions on Fifth

Dinner Sponsored by Nancy and Michael Murphy

Subscribe to TABLE Magazine’s print edition.