What is a museum? Word-based art in the Carnegie Museum of Art’s lobby nudges us to ponder the topic. The banners of Andrea Geyer’s Manifest billow gently against the windows of the stairway to the Scaife wing’s galleries. Among their several declarations: “I want a museum to recognize that for culture to take place our bodies must appear,” and “I want a museum to be a space for breath.” The artist challenges viewers to think critically of the museum before they even engage with the work shown within it. Similarly, Gala Porras-Kim’s The reflection at the threshold of a categorical division takes the Carnegie’s archives to task in the Forum Gallery in the main lobby.

Her focus is ostensibly simple: Objects within the museum shuffled between the Carnegie Library, the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and the museum of art. In considering their virtues, or possibly their lack thereof, Porras-Kim just asks: Why?

Porras-Kim embodies the role of the artist as a sort of chameleon, trickster, and rabble-rouser. While she works with objects in sterile archival environments, Porras-Kim herself is jocular and warm, qualities that come across in her work. In the letters she writes to museum officials asking them about their archives, she signs each with “Sincerely.” There is a sincerity to the work. What might seem ironic or cold in someone else’s vision is deeply, almost uncomfortably sincere. Porras-Kim does not ask museums to apologize or make floundering acknowledgments. She only asks them—and us—to look.

Sincerely, Gala Porras-Kim

The topic of museums unjustly holding sacred cultural objects is not new. However, Porras-Kim takes these questions beyond human pursuits. In research on objects from Chichén Itzá sitting in Harvard’s Peabody Museum, Porras-Kim writes that “It is clear from documents regarding the provenance of these objects that human laws were used to displace them from their current location at the Peabody. Their owner, the rain, is still around.”

She is not suggesting repatriation. The artist instead envisions the objects as what they are: sacred objects belonging to the Mayan rain god Chaac. She has a radical earnestness you often only see in activists, people like Temple Grandin or Greta Thunberg who espouse the views they do because they simply can’t imagine thinking any other way. But Porras-Kim’s work does not see itself as providing answers, but rather to ask questions.

Part of Porras-Kim’s interrogation involves fakes, like western interpretations of East Asian pottery when that was en vogue or bold-faced forgeries of art objects with nowhere else to go. These things sit in museum archives alongside real sacred objects. Classification numbers and top-line descriptions reveal some truth about the objects, but the viewer begins to sense that the imposition of meaning that shades everything in the collection. Some truth is far, far more complicated than the simple trust we’ve been trained to place in museums and what they share with us. And how they share it.

The Carnegie Museum’s Reflection of Itself

The Carnegie has considered the question of museum ethics in its internal systems. The Egyptian wing of the Natural History Museum, which once held human remains, has changed its presentation and removed those objects. Porras-Kim’s work does not take that low hanging fruit and instead leans into a broader statement. The Carnegie Institute is in a unique position for questions about categorization as two museums and a library under one institutional umbrella.

There is also a larger, even more confounding question at stake within Porras-Kim’s work. Everything that is The Andy Warhol Museum, The Kamin Science Center, The Carnegie Museum of Art, The Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and the oft-forgotten Powdermill Nature Reserve is all one business entity. How do those thresholds of categorization color the meaning of what we experience within their precincts? How do they shape access or lack thereof to the roughly 23,000,000 objects owned and cared for by these institutions.

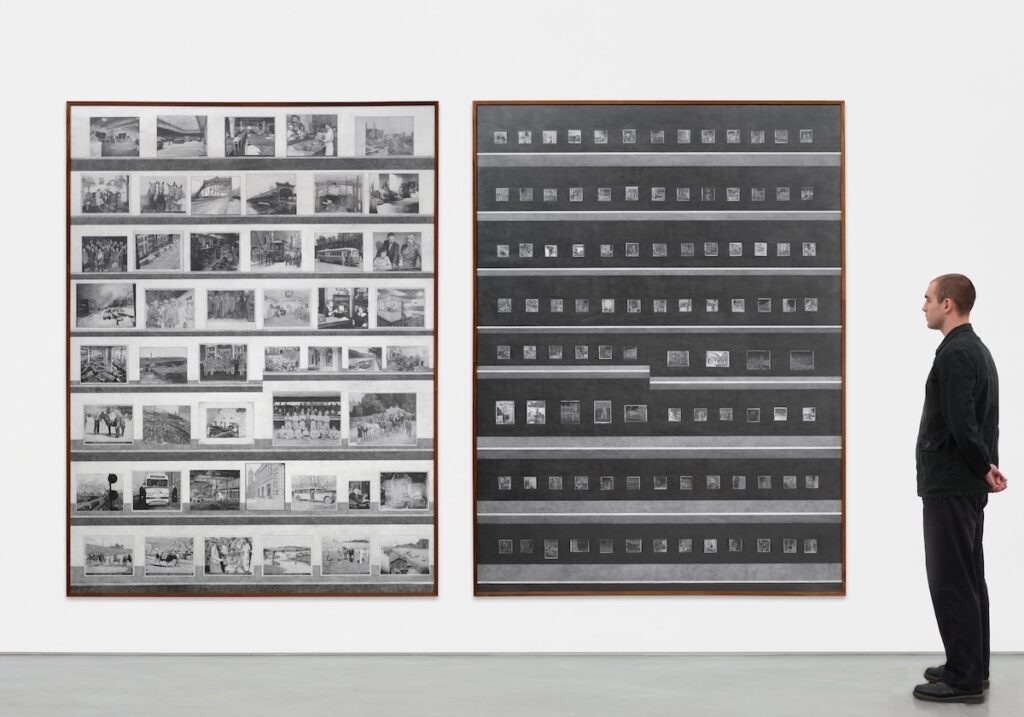

The five large graphite works Porras-Kim produced for the show gesture at just how much of a museum is in its archives. They depict 75 snuff bottles. 147 photographs. 202 mineral objects. There are moments of interest, a tiny jade ibis, a round piece of garnet, an oddly phallic, kitschy statue, a negative of four horses at an Allegheny County Fair. Porras-Kim situates each object on an imaginary shelf, complete with its penciled-in shadow. But you will likely never see any of those objects in their actuality. No one will. All you get is shadows, formless döppelgangers.

A Small Box of Fleas

The piéce de resistance for Porras-Kim’s concept, though, is Least likely to be on view, a series where Porras-Kim asked museum workers what piece they thought was least likely to be on view in their institutions. The results are illuminating. Though some are obvious, things that are too big or too fragile, others are fascinating and amusing.

A crowd-pleaser Porras-Kim points out is “a small box of fleas” not shown because of “lack of immediate context.” What is the immediate context for showing a small box of fleas? Certain objects create a sort of Möbius strip of bizarre logic. One “least likely” is installation made of hundreds of small, sharp objects that the artist requested have no safety measures around it—therefore no one will ever see it. Similarly, a large fluorescent painting that conservators determine would decay if it sees the light of day will languish forever in an archive. What, then is even the point of a museum having such objects? If museums are gatekeepers, bastions of culture, is culture meant to sit in a vault for eternity?

Another real-time example of Porras-Kim’s concepts within the museum is the Charles “Teenie” Harris photography archive. The Carnegie Museum of Art owns Harris’s entire catalogue and employed a contemporary of his to oversee the archive and contextualize it. The photographs were photojournalism, initially, not artwork. However, to those who knew Harris, his photographs might not be in the same category as, say, an artwork by Keith Haring, a deceased artist they had never met. Objects removed from their context change. In Least likely to be on view, one work by a photojournalist was too personal to show. There’s no indication about what it was. However, it lays bare the processes the Carnegie itself did for Harris’s archive, which now is finally out in the open.

Art is as We Are

There’s a saying that “the world is as you are.” Art, too, is the people who look at it. The flowery figurines and precious snuff bottles Porras-Kim depicts were once valuable to someone. (Will colorful, discarded vapes one day sit along with them in a museum archive?) If we view work with curiosity and openness, we will see more in it. The Carnegie Museum’ of Art’s willingness to engage with its own work is brave, and Porras-Kim’s interrogation of it equally so.

One thing that’s refreshing about Porras-Kim’s approach is that it does not postulate institutional change. Too often, museums put together exhibitions that proclaim change-making and radicalism but do that by…putting art on a wall in a white cube. What a radical act! Nowhere does Porras-Kim call you into a webinar on the changing role of museums or a human-resources sponsored support group. Museums do have a role to play, and a vital one at that, in a changing political landscape. She allows objects in museums to be what they are, just objects. Everything else is up to us. Is the museum a sacred space, an academic institution, a commercial business, a leisure playground, or an educational resource? The answer to all of those questions is yes.

Story by Emma Riva

Photo courtesy of the Carnegie Museum of Art

Subscribe to TABLE Magazine’s print edition.