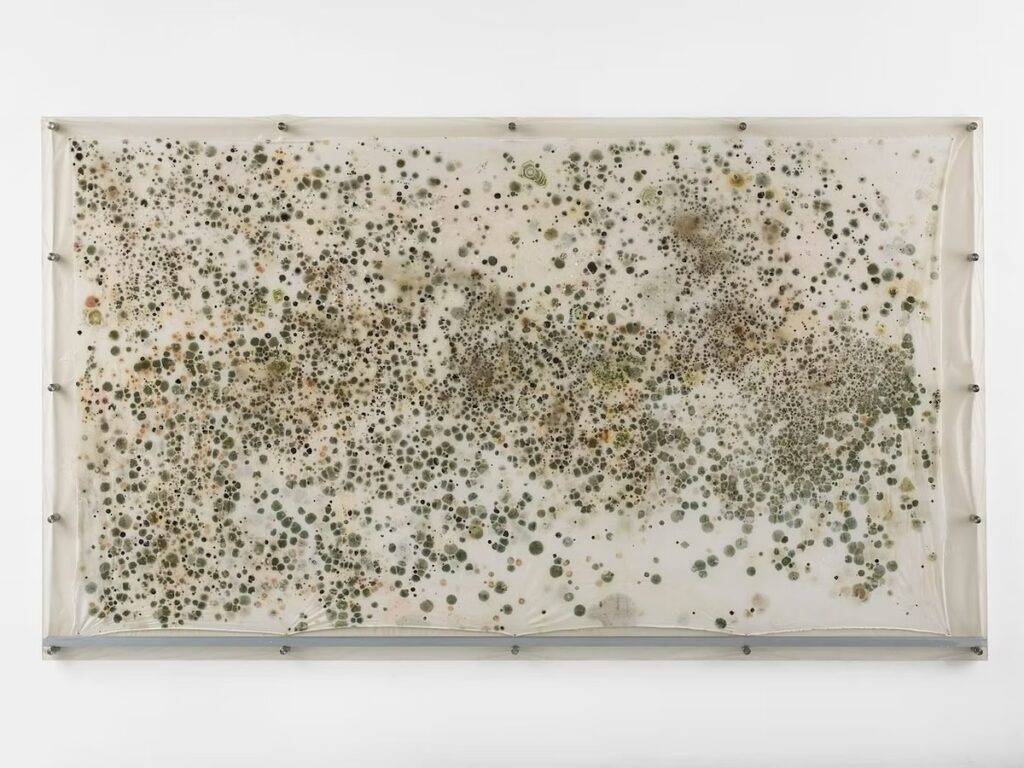

“Is that…mold?” I turned to my boyfriend with a mixture of incredulity and delight at what I saw on the wall of Cleveland’s Museum of Contemporary Art. Mold does not typically inspire such a response. Taupe spores propagated into soft shapes, indistinguishable from light splashes of watercolor on a swath of muslin. For this piece, Out of an instance of expiration comes a perennial showing, Colombian artist Gala Porras-Kim extracted mold spores from the British museum. She then placed them on a sheet and brought them to MoCa Cleveland.

One of the destructive elements against which museum curators fight mightily was brought front and center as something that the curators here were responsible for protecting and preserving. I couldn’t stop talking about “the mold piece” for a week straight.

If you look at enough contemporary art, you can get somewhat numb to its tropes. Oh, great, another way to juxtapose the archive as liberation with the deconstruction of preconceived hierarchy of cultural values and assumptions of artistic worth. Blah. Back to doomscrolling. However, Porras-Kim’s work elicits a real, disruptive reaction, which in the current contemporary art landscape is worth its weight in gold.

Archival Disruptor Gala Porras-Kim to Debut New Work at Carnegie Museum of Art

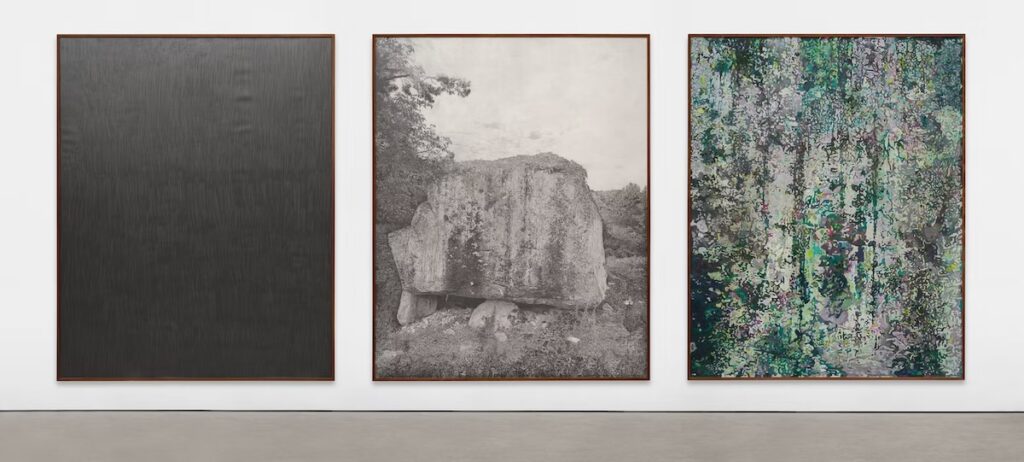

In the full show at moCa, A Hand in Nature, Porras-Kim showed an ability to work both big and small. The pieces she makes call to mind both the overwhelming sublimity of ancient structures and the granular bureaucracy of the archives that hold them. I was hooked on her vision. It was a wry take on the ethics of museum collections combined with a deeply felt interest in objects. She created enormous paintings that imagined what the world looked like from the inside of a stone monolith. I rarely see single-artist museum shows that show such a wide variety of mediums in such a cohesive way. Then, less than a week later, I learned Porras-Kim would be coming to Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art for a show in their Forum Gallery.

Porras-Kim’s subject matter is not a new one. Many artists have questioned the institutions that hold their work. The Carnegie has done this themselves with Amie Siegel’s Panorama in 2023. What sets Porras-Kim apart is her bold, earnest, and curious approach.

Art Can Be Both Beautiful and Provocative

In A Hand in Nature, she presented many of her paintings with letters she wrote to museums in Mexico, the United Kingdom, and South Korea asking the curators to consider the ritual nature of the objects they hold. Perhaps it sounds a little supernatural, but one gets the sense that Porras-Kim can feel the objects’ souls. The most talented artists are attuned to medium—a painter should love and wrestle with paint, a sculptor should know stone intimately. Porras-Kim is gifted at multimedia, participatory, and time-based work.

Gala Porras-Kim Takes the Carnegie

The reflection at the threshold of a categorical division, opening on February 27, will see Porras-Kim using objects from the archives of the Carnegie Library, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and Carnegie Museum of Art. The Carnegie holds a deep, meticulous archive of work from the three institutions within it.

So, Porras-Kim has had the opportunity to dive into a plethora of museum items. “Some of the works are about how the collection moves between different parts of the Carnegie and how choices were made over objects and where they are situated today (library, CMOA or CNMH),” Porras-Kim told TABLE.

Art and Objects

The work in The reflection at the threshold of a categorical division looks at identical or similar objects across the three institutions, some designated as “art” and simply “objects.” Porras-Kim created several large-scale two-dimensional works like The Weight of the Patina of Time, using graphite and colored pencils to depict snuff bottles, ivory sculptures, and gems.

Porras-Kim’s father is a historian. So, she spent much of her childhood getting to look at the archival materials her father was pouring through. She often found herself making pencil drawings based on what she saw. “I drew a grey blob that I marked ‘dinosaur poop.’ These days, I feel like I do basically the same thing,” she remembered.

She noted that “the taxonomy of these things dictate the choreography of how people interact with them.” In the center of the Forum, she placed a sculpture made of windows from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The window was taken out as part of an ongoing restoration in the Met, and they offered it to Porras-Kim. In the Carnegie, she placed it in the center of the Forum, where the light hits it.

Engaging with the Collection

One of the traps that plague many shows dealing with both what’s in the archive as well as the rules governing that archive, is a sort of over-analysis where there’s little consideration of the actual work. Porras-Kim’s work does the opposite. It asks us to step back from “academic word salad” to really feel and think for a moment, based on the physical reality of what’s in front of us. For example: How does it make any sense for a museum to have bodily remains in its collection? Is it acceptable to display objects of religious reverence in a white cube, deprived of the environment that sheltered them and provided greater meaning?

For The reflection at the threshold of a categorical division Porras-Kim also took a survey of museum workers around the country to ask what the “least likely to be on view” element of their collections was. She then generated images of those objects, with a letter accompanying it asking why these particular objects weren’t on view. “There could be infinite taxonomies. The mold has its own way of looking at the hierarchy of the world,” Porras-Kim said.”These new taxonomies are additive.”

What Art Can Be

Art shouldn’t just be for insiders, and it shouldn’t just confirm your existing belief system. It should in fact encourage you to think differently about what you see. Porras-Kim’s work recontextualizes the objects. It’s worth seeing, even if you think art isn’t “for you.” Porras-Kim’s work pushes the boundaries of what art is in the first place. The winter is drab, the news cycle is depressing. NASA announced a city-killing asteroid has a 3.1% chance of hitting earth in seven years. Art should provoke something in you. It can be a question, a twinge of confusion, or a moment of awe at what’s in front you. Life is short. Let objects make you feel something, whatever institutional label they’re under.

Story by Emma Riva

Cover image: 530 national treasures (detail), 2023, colored pencil and flashe on paper, Courtesy of the artist.

Subscribe to TABLE Magazine‘s print edition.