The best art requires only that you are human and capable of feeling to understand it. While an art history degree or some technical knowledge can be helpful, art at its core is human beings struggling to understand the messy project that is birth, life, love, and death. Silver Eye Center for Photography’s Fellowship 25 lets viewers into domestic spaces, intimate moments, and private experiences that harness that universal human core behind artmaking.

A key moment of this principle in action is Brett Davis’s 88 stills, made in collaboration with his daughter, Toko. Davis leaves a lot of space around each image set on the wall. The negative space shows that Toko has room to grow and change. It’s unbelievably tender and sweet. One of photography’s greatest gifts is its ability to portray looking at another person with love, and Davis and Toko’s work is a shining example of that. The images have a scrapbook-like quality to them. The motion blur of a playground swing, the soulful eyes of a dog, and the smiling stitched face of a stuffed animal all show the world through Toko’s eyes. Davis and Toko worked side by side to hang the video stills.

Silver Eye Center’s Fellowship 25 Highlights Love and Death

Curator Helen Trompeteler noted that Davis told Silver Eye the exact heights to hang everything at so that a child like Toko could see it. Viewers have to kneel down and imagine themselves in her perspective. In his artist statement, Davis describes himself as a “partner, father, and artist” de-centering the expected hierarchy.

Something that caught my eye multiple times in Fellowship 25 overall was the way the artists presented themselves in their written biographies. It’s an unexpected place to find meaning and extra context for the show. There’s an intimate honesty to all of them, with questions about their practice that complements the images on the wall embedded in their how they talk about themselves.

Nearby, Paolo Morales’s photographs focus on the relationship between mother and adult son, in contrast and conversation with Davis’s theme of an adult father and a toddler-age daughter. In one image, Morales’s mother lays down at a hairdresser with her wet hair in a bathing still. It shows the hair salon as a site of care and community.

Intimacy and Binaries

Pittsburgh-based Clare Sheedy writes that she “teaches art to children and works at a Downtown box office.” It was striking and meaningful to me to hear a creative person not working in academia and proudly looping their other professional vocations into their identity. It’s affirmative and meaningful for that to be out in the open, when so many in creative fields are working multiple gigs to get by.

Sheedy’s photographs are part of a series entitled parts of a bird where she combines photographs with a poem in braille. Viewers can touch the braille, but not the photograph. A genius move in Sheedy’s presentation of parts of a bird is to place braille lettering on either side of a tender nude photograph. You can touch the braille, but not the body, even as the body is in an intimately vulnerable state.

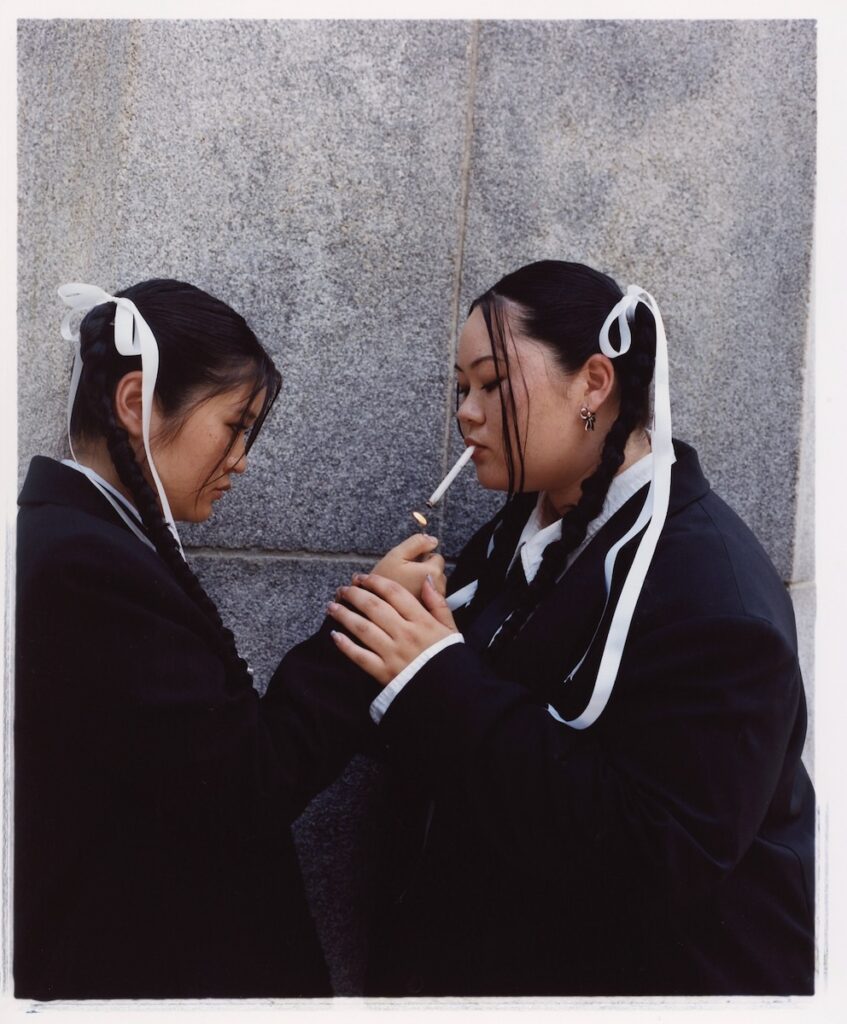

A favorite image of mine is Ramona Jingru Wang’s Sukeban Girls. It made me think of a much-lauded scene in Ryan Coogler’s 2025 film Sinners. Smoke (played by Michael B. Jordan) lights his brother Stack (also played by Michael B. Jordan)’s cigarette. It’s highly technical movie magic, but also could be material for a surrealist painting. Jingru Wang’s photograph shows two women dressed identically, white ribbons in their dark double braids, one lighting the other’s cigarette. It brings out the intimacy of lighting a cigarette. There are subtle differences between the two women. The photo speaks deeply about how same-gender friendships and intimacy often feel like sister bonds. Jingru Wang took inspiration from Park Chan-Wook’s filmography and the depictions of Asians as cyborgs in sci-fi films for the photo series, called My friends are cyborgs but that’s ok.

The Self and Nature

Alana Perino also engages with the self and, like Davis, has low hanging work that you have to kneel to look at. Perino’s evocation of growing in New York City, the North Fork of Long Island, and “the stretch of Highway between the two” shows up in their work in its liminal nature. Their images have figures and moments, but no visible faces. A figure with a memorial tattoo on their back reminded me of Keiko Fukazawa’s work with incarcerated youth where she photographed commemorative tattoos. The images came out of deaths in Perino’s family and confronting questions about mortality.

Of the work in the show, Sobia Ahmad’s draws most directly from the natural world. Ahmad’s photographs in Fellowship 25 are part of her ongoing project of documenting the Pando forest in Utah. Pando is an aspen forest all growing from one interconnected root system. Ahmad’s tree works are recognizable to anyone who’s stopped to look at her public installation on Liberty Avenue. What stood out to me most about Ahmad’s images were their inversions. Ahmad took the photos on reversal film stock and printed them as negatives. There’s a mystical or ghostly quality to the images, as if you’re seeing visuals from a dream. Her photographs reveal a reality underneath our reality, in line with her interest in Sufism and mystic traditions.

Universal Love

A show like Fellowship 25 faces the challenge of putting different artists’ work together to create a cohesive whole. This iteration of Silver Eye’s fellowship focuses on love and caring. Jingru Wang, Sheedy, and Davis shine with their eye for balancing staged photographs and moments of candid intimacy. Fellowship 25 engages with universal questions: Who are we as people? Who do we want to be? What does it mean to be human? Often contemporary art narrows itself into granular categories. Fellowship 25, however, is a breath of fresh air in how it feels both sweeping and defined. The show seems to want you to linger, a respite from the hostility that art spaces often have.

Story by Emma Riva

Images courtesy of Silver Eye Center for Photography

Cover image by Brett Davis

Subscribe to TABLE Magazine’s print edition.